Contents

Introduction

The Hydra and Tesla machines have a RISC-V toolchain, which includes the compiler, assembler, and linker, as well as an emulator that automatically runs when a RISC-V program is executed. This means that for the most part, it is seamless to you.

To avoid name conflicts, all of the RISC-V tools are prefixed with riscv on the Hydra and Tesla machines. For example, riscv-g++ is the C++ compiler for RISC-V code.

Writing and Running RISC-V Programs

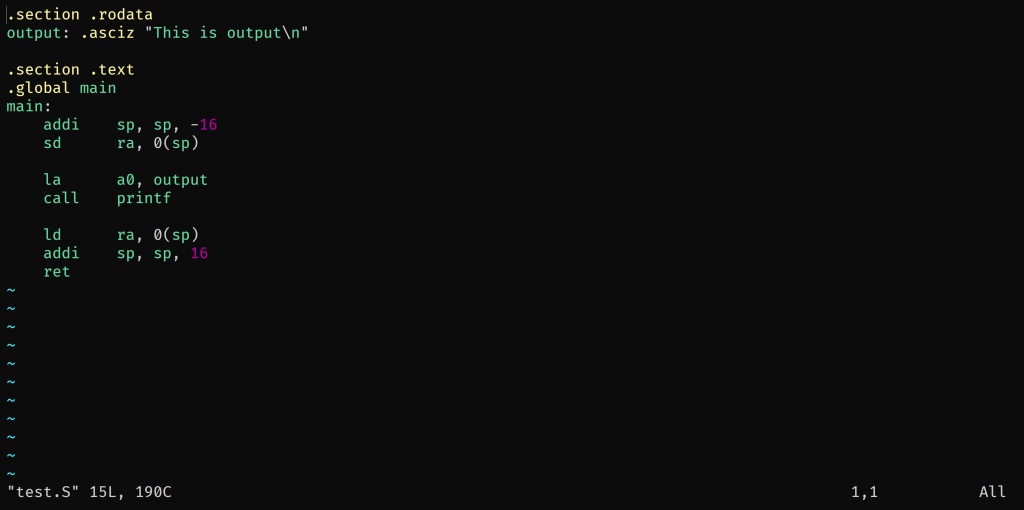

You will edit your RISC-V assembly and C++ files just like you would your normal labs for your other classes–either through VIM or some other text editor.

NOTE: Unlike RARS, which uses the extension .asm, all RISC-V assembly programs using this system will have the extension .s.

After we are done editing out assembly file, we can assemble it using the G++ compiler. Luckily, it knows based off of the extension (.s) that it doesn’t need to compile and it will just invoke the assembler and linker. The extension is case sensitive. A capital .S will invoke the preprocessor first, whereas the .s will not.

~> riscv-g++ -o test test.s ~> ./test This is output ~>

As you can see, we can execute the RISC-V program directly on the Hydra and Tesla machines, even though these machines are Intel x86/64. This is because of a system on Linux that will allow you to specify how to run a non-native program. Which, in our case, runs the emulator called qemu-riscv64.

~> cat /etc/binfmt.d/riscv64.conf :riscv64:M: :\x7fELF\x02\x01\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\xf3\x00 :\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\x00\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff :/opt/eecs/root/bin/qemu-riscv64: ~>

This mess may look complicated, but what it’s doing is looking at a specific field. The \x7fELF is the start of all executable programs, and what it’s looking for is the magic value \xf3, which is how the executable file defines that this is targeted towards a RISC-V machine. If you ever take my COSC562, we will actually read these ELF files and run them.

Labels

A label marks a memory address with a name, much like a function name in C++. Labels in assembly end in a colon ‘:’, which makes them easy to identify. A label must be unique in assembly. When you create a function in C, the name of the function becomes a label. These labels mark the memory address of the first instruction to run in the function. The following shows an example of a label.

.section .rodata

output: .asciz "Hello World!\n"

.section .text

.global myfunc

myfunc:

addi sp, sp, -16

sd ra, 0(sp)

la a0, output

call printf

ld ra, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

ret

Numeric Labels

Numeric labels are labels that just contain a number. These labels are not added to the executable and are only used by the assembler for jump and branch information. When referring to a numeric label, we use its number followed by a suffix of either b or f. The b stands for “backwards” and the f stands for “forwards”. We can have numbers backwards from the instruction or forwards from the instruction. For example, here is a for loop in assembly using numeric labels.

# for (i = 0;i < 10;i++)

li t0, 0 # iterator

li t1, 10 # ending

# First numeric label, 1. We can call it any

# number we want.

1:

# if (t0 > t1) goto 1 "forward" which is

# the label down below.

bge t0, t1, 1f

# Body would go here

# Execute the step (i++)

addi t0, t0, 1

# Jump to the label 1 "backwards", which jumps up to

# the start of the for loop.

j 1b

1:

Assembler Directives

An assembler directive directs the assembler to change how it assembles. In other words, these are not instructions, but rather, directives given to the assembler. Assembler directives begin with a period ‘.’, which makes them easy to identify.

The following table summarizes many of the assembler directives. Afterward, we will see several examples using assembler directives.

| Directive | Description |

|---|---|

| .section X | Switches sections, such as .section .text (text section), .section .rodata (R/O data section). |

| .global X | Makes a label global, such as .global main or .global myfunc. A global label can be seen by the linker, and is required if the symbol is called from a different object file. |

| .asciz X | Creates an ASCII string with a zero on the end (C-style string), such as .asciz “Hello World\n” |

| .byte X | Creates a 1-byte value and assigns it to X, such as .byte 33 |

| .half X | Creates a 2-byte value and assigns it to X, such as .half 122 |

| .word X | Creates a 4-byte value and assigns it to X, such as .word 77 |

| .dword X | Creates an 8-byte value and assigns it to X, such as .dword 112233 |

| .float X | Creates a 4-byte, IEEE-754 value and assigns it to X, such as .float 22.75 |

| .double X | Creates an 8-byte, IEEE-754 value and assigns it to X, such as .double 112233.4455 |

These directives, such as .half, .word, .float, are usually used to create global values. We don’t use them except for maybe to create constants in the .rodata section. Many times, we will use a label to mark the memory address the assembler will put these values.

.section .rodata

output: .asciz "%s %d %d %d %ld\n"

str_output: .asciz "This is a string:"

byte_output: .byte 33

half_output: .half 177

word_output: .word 19918

dword_output: .dword -19922

.section .text

.global myfunc

myfunc:

addi sp, sp, -16

sd ra, 0(sp)

la a0, output

la a1, str_output

la a2, byte_output

lb a2, (a2)

la a3, half_output

lh a3, (a3)

la a4, word_output

lw a4, (a4)

la a5, dword_output

ld a5, (a5)

call printf

ld ra, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

ret

When ran, the code above prints the following output: This is a string: 33 177 19918 -19922. Recall that we normally wouldn’t do this because we just created a bunch of constants in global memory space, but this shows several ways to create data in assembly.

Merging C++ and Assembly

Unlike RARS, we have the full power of C/C++. Unfortunately, C++ is a little difficult to write raw assembly for, so instead, we will turn off a lot of the C++ features to make it easier on ourselves.

One of those features is “overloading”, meaning we can have two or more functions with the same name, and C++ will choose which one to execute based off of its parameter list. You will see extern "C" blocks in a lot of this code. This tells C++ that it needs to treat whatever is in the block as old C code instead of adding the newer C++ features.

Calling Assembly from C++

Calling assembly from C++ is a matter of just combining both files when you compile. The linker stage is responsible for making sure all of your source code gets linked together.

When calling assembly from C++, all we need to do is prototype the assembly functions in C++. We do not define the functions in C++, since those functions will be defined in assembly. Below is an example of such a program.

#include <iostream>

#include <sstream>

using namespace std;

// This is important to tell C++ not to look for a mangled

// name.

extern "C" {

double sub(double a, double b);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc < 3) {

cout << "Usage: " << argv[0] << " <left> <right>\n";

return -1;

}

double left;

double right;

double result;

// We should error check, but for demonstration purposes, we don't

istringstream sin(argv[1]);

sin >> left;

sin.clear();

sin.str(argv[2]);

sin >> right;

// Notice sub below is only prototyped so C++ knows what parameters

// to give it.

result = sub(left, right);

cout << "Result = " << result << '\n';

}

So, we wrap the sub prototype in extern “C” so that C++ won’t mangle the name. When we prototype, all C++ is going to do is error check the name, parameters, and return type. C++ doesn’t know what the function does, but it doesn’t need to.

The linker will then look for a symbol called sub, which is why we make it global below. The linker will find this symbol in our assembly file.

.section .text

.global sub

sub:

# fa0 - left

# fa1 - right

fsub.d fa0, fa0, fa1

ret

C++ follows the RISC-V ABI, meaning that the arguments go in a0, a1, a2, etc. and for floating-point arguments fa0, fa1, fa2, etc. This is why it is important to know the RISC-V ABI. We can’t just randomly choose registers when it comes to the arguments and return value. We must also ensure that if we use the stack, we align it properly to a multiple of 16 bytes.

The code above produces the following result:

~> riscv-g++ -o testasm testasm.cpp testasm.s ~> ./testasm 10.7 2.5 Result = 8.2 ~>

Calling C++ from Assembly

Since all the linker does is look for symbols regardless of the programming language, we can also call C++ functions inside of assembly. When we add a label in assembly, the linker is responsible for finding it. If it can’t find it, we will get a linker error (called an ld error).

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// Prototypes

extern "C" {

long do_divide(long a, long b);

}

// Definition

long do_divide(long a, long b) {

cout << "I'm in C++!\n";

return a / b;

}

// There is no int main() here since we define it in assembly.

Notice the extern “C” in this case only encapsulates the prototype. C++ doesn’t need one for the definition if the prototype is setup properly.

.section .rodata

output: .asciz "Result = %ld\n"

.section .text

.global main

main:

addi sp, sp, -16

# Need to save RA since we're making function calls

sd ra, 0(sp)

# Set up registers for function

li a0, 7

li a1, 2

call do_divide

# Move the result (a0) into a1

mv a1, a0

la a0, output

call printf

# Restore original RA

ld ra, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

# Return 0

li a0, 0

ret

Notice how we pass 7 in for the first argument in a0, 2 for the second argument in a1. When divided, we get the integer division of 7 / 3 which gives us 3. The code above produces the following output.

~> riscv-g++ -o fromasm fromasm.cpp fromasm.s ~> ./fromasm I'm in C++! Result = 3 ~>